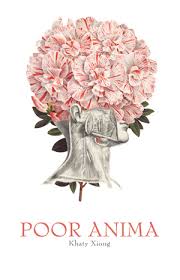

Some Notes & a Cento for Khaty Xiong’s Poor Anima

by José Angel Araguz

Je est un autre (I is another). – Arthur Rimbaud

This quote from one of Arthur Rimbaud’s letters kept coming to mind while reading Khaty Xiong’s collection, Poor Anima (Apogee Press, 2015), at first because of the poet’s borrowing of lines and titles from Rimbaud’s work, but later because of its connection to the book’s running theme of the elusive self. Rimbaud’s quote, “I is another,” which can be interpreted to mean that our concept of self or “I” is separate from our inner selves, seems a natural conclusion within the context of the poetic act. This idea walks the fine line between persona and lyric self, and creates a space for emotional authenticity. These words also carry an added charge when considered within the world of Xiong’s poems, a world of bicultural identity, where the “I” is another in not one but two languages.

With these thoughts in mind, it is telling to look at the opening poem, “Refine,” and note how it reads as if fighting against having a first-person speaker. Without an “I,” the reader feels an added insistence to focus on the opening image:

—two bodies tangled in the night

cutting, pleading

her dark wet form against the darker form

This image is followed by a series of questions:

what does love look like now?

why would anyone want to write this?

what is vulnerable?

Again, without an “I,” these questions feel like they are coming out of a void, their need to be asked more urgent than a need for authorial presence. In dealing with the braided narratives of war, exile, and family, the poems of Poor Anima alternate between this “distanced” type of speaker and an “I” that is right in the mix of meaning-making. Note that by “distanced” I don’t mean abstract or objective; rather, Xiong is able to bring herself under as much lyric scrutiny as any family story or linguistic concept. In this way, Rimbaud’s “I is another” becomes a creative act, one that allows a poet to directly trouble and be troubled by various aspects of the lyric self.

In working on this cento, I specifically sought out lines that had an “I” in them. I thought doing so would unravel a hidden theme or argument in the book. The resulting cento gives examples of the linguistic elasticity that Xiong’s work seeks to engage with. The opening couplet consists of lines from the title poem and from “Bad Blood,” the latter’s title taken from Rimbaud:

When I linger awhile longer and I want my mother

I mean language touched by letters, the ones that teach surrender.

While my means of bringing these lines together was intuitive, I feel these two lines on their own speak to the spirit of the book in their respective ways; when brought together, they create a new depth. In “Poor Anima,” the line “When I linger awhile longer and I want my mother,” is one of a list of “when” statements. Each statement feels unfinished, yet they accumulate into narrative and dialogue grounded in the speculation of the word when, which implies a specific time but also the suddenness of transition via cause and effect.

The line from “Bad Blood” above is the last line of Xiong’s poem, and is preceded by a meditation that starts, “The dead return.” This opening phrase is echoed later in the poem by “Exile opens such possibility, and ghosts remind you to care.” Both of these instances point to the last line’s idea of being taught “surrender.” There is tension implied in this poem between the living and the dead, one that points to the creative space of meaning. The dichotomy of the living and the dead also implies transition. Ultimately, to make peace between the self that is “I” and the self one lives in, one must make peace with the changeable nature of meaning. Which brings us back to the questions of the opening poem:

what does love look like now?

why would anyone want to write this?

what is vulnerable?

The book and statement that is Poor Anima stands as an answer to all three.

Poor An(i)ma: a cento with lines from Khaty Xiong’s Poor Anima

Je est un autre (I is another). – Arthur Rimbaud

When I linger awhile longer and I want my mother

I mean language touched by letters, the ones that teach surrender.

Often, I call to lure myself—

I am American and it means something: My family,

the others I can’t quite trace out

though I harrow,

this time a depression, etc. I hand over my species,

what a fucking mess. I guess we earned it—

seasons in words. I am your keeper.

I can’t hold this form, can barely remember how

I abuse the season for dialogue.

I mourn the living;

that gives river a new delta. I wait—go on—the same way.

I have been writing other things: other things have been writing me.

José Angel Araguz is a CantoMundo fellow and the author of seven chapbooks as well as the collections Everything We Think We Hear (Floricanto Press) and Small Fires (FutureCycle Press). His poems, prose, and reviews have appeared in Crab Creek Review, Prairie Schooner, The Windward Review, and The Bind. He runs the poetry blog The Friday Influence and teaches English and creative writing at Linfield College in McMinnville, Oregon.