Epistles from the Poetics of Fury: An Interview in Correspondences

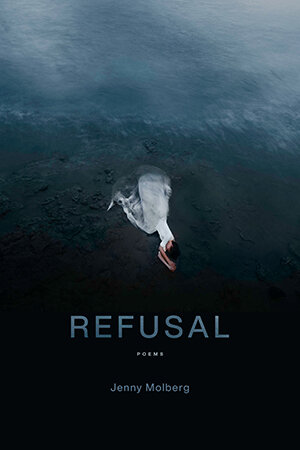

by Jenny Molberg, author of Refusal (LSU, 2020) & Kathryn Nuernberger, author of RUE (BOA, 2020)

Dear Jenny,

Your new book, Refusal, embraces and reinvents the epistolary form. And my new book, RUE, was inspired in part by a series of letters I received that seemed to reach me across a distance much vaster than just a few thousand miles.

We’ve had so many inspiring conversations, often in epistolary form via email and messenger. Wouldn’t it be great if we had an epistolary interview with each other about these poetry collections we worked on side-by-side?

If so, I would start by asking about your epigraph from Adrienne Rich’s “When We Dead Awaken”: “And this drive to self-knowledge, for woman, is more than a search for identity: it is part of her refusal of the self-destructiveness of male-dominated society.”

This essay of Rich’s has also been a touchstone for me in recent years. How has Rich’s work shaped Refusal?

~

Dear Kate,

I read Rich’s "When We Dead Awaken" long ago, but encountered it again as I was finishing up Refusal and the essay took on a new life. I got married when I didn't really want to; I was subsequently divorced; I had experienced emotional and verbal abuse, gaslighting, and a sense that to have a career in writing, one that is both social and intellectual, I must stay quiet, keep my head down, and expect a patriarchal resistance against female or non-binary success in the literary world. I realized that over the years I thought it was my duty to play the role of a muse, and to consider my work as secondary to a stereotype of male genius. I'd spent years cultivating a poetics that was intentionally not angry, not political—detached —and found myself thinking I'd robbed myself of the ability to be genuine in my work.

When Rich writes, "It is the tone of a woman almost in touch with her anger, who is determined not to appear angry, who is willing herself to be calm, detached, and even charming in a roomful of men where things have been said which are attacks on her very integrity," I thought ah—of course. I thought I deserved those attacks on my integrity. And suddenly every piece of criticism, craft, or theory that set out to subjugate the female body and experience rose to the surface as bullshit.

Speaking of “When We Dead Awaken,” I’d love to talk about your poem by the same title. I was just wondering out loud the other day about how so many cultures have a version of the Lady of the Lake story—is this a form of the muse—the popular image of the pure, white, female ghost who rises out her violent death, who haunts her own watery grave? Your poem, which ends in a kind of witchy resurrection and a refusal to accept the death of a pregnant girl by the hands of her boyfriend, was one that I returned to again and again. What do you think is the relationship between the imagination and anger?

~

Dear Jenny,

What you say about feeling as if you’d lost your genuine voice inside a performance of subservience really resonates with me. I was once a person who worked really hard to be judicious, thoughtful, nice in all of my interactions. Constantly bending my rhetoric so I wouldn't hurt feelings or seem unreasonable in my progressive feminist perspectives, I often felt so twisted up after a simple conversation at the grocery store. The Adrienne Rich line that came as a lifeline to me is from "On Lies, Secrets, and Silence":

“The possibilities that exist between two people, or among a group of people, are a kind of alchemy. They are the most interesting thing in life. The liar is someone who keeps losing sight of these possibilities.”

I realized that by sublimating my anger in a performance of social niceties I was actually giving up on the possibility of ever feeling meaningfully connected to anyone again. My definition for nice had been all wrong. Niceness is the word for "fake as fucking shit." Niceness is the word for protecting racist, sexist, transphobic, heteronormative hierarchies with a big awful smile plastered on your face.

My friendship with you, Jenny, was one of the first to emerge in the wake of what I was thinking of then as "my experiments with honesty" and it was the kind of connection that encouraged me to keep going. To believe that even though I felt like a wrecking ball in my marriage, in the office, in all these corners of my life, that it was worth it to keep trying.

We were on a panel about women's anger not too long ago and a key throughline from that conversation which I see echoed in your book, is the way anger differs from other feelings in the way the expression of it can be a form of political action. Can you talk about how you found ways to make anger a force of positive momentum in Refusal?

~

Dear Kate,

Thank you for saying that about our friendship! I feel the same way, as you carved out a space for me in a life of poetry and academia when we were working together in rural Missouri—a place not always welcome to either of us. Maya Angelou says, "Bitterness is like cancer. It eats upon the host. But anger is like fire. It burns it all clean."

In our panel on "The Poetics of Fury," and in many of my female friendships, I've found solace in the ability to recognize each other's anger: female friendship as a collective force that can create change. This is one of the reasons why I decided to address the epistolary poems in my book to my friends. I think female friendship is inherently political, because, as I've seen in my own life, it can make some perpetrators or predators very angry if they feel excluded or taken to task. We create a kind of secret language to warn the herd or troop against a predator. I've begun to think of my poems as little calls in the wild to readers who may speak this language or identify with it. Though the poems were difficult to write, and I'm still afraid of many of them, I want their message to be one of solidarity and fight. Sometimes this fight is not just personal, but public, as we saw with the Brett Kavanaugh hearings, and it sheds light on the way our political and legal systems perform a private oppression on a public stage.

I am struck by your poem, “Poor Crow’s Got Too Much Fight to Live,” especially thinking about Confessionalism and the ways in which poems as artifacts can and cannot hold up in a court of law. You write at the end of the poem, “I’m sorry, other people he might have or still yet / hurt, but I’m not so naively idealistic as to think / any good could come of saying to the public that I was / assaulted by an OB/GYN in his office in Logan, OH / in May 2010 and I’m willing to testify to that.” Clearly, the speaker knows that this declaration is both “saying to the public” and not, as it lives inside a poem. What are your thoughts on the idea of a poem serving as a kind of testimony?

~

Dear Jenny,

We both know so well all the ways the criminal justice system is designed to keep us quiet, afraid, and convinced we must not be understanding something we are in fact understanding all too well. Because if we do understand everything, then the only conclusion is that we are facing a panel or a committee or an officer or a boss who sees people like us as means to their own ends. I love the line you have for this feeling of realizing what the authorities think of difficult women. In "Epistle from the Hospital for Text-Messaging" you write, "Something I don’t understand about myself / makes people want to hurt me."

I know one person can't beat this legal system, which misunderstands justice as the protection of one particular kind of power and order. As I was writing “Poor Crow…” I was following Emma Sulkowicz’s performance art piece “Carry That Weight” and how they carried a mattress around Columbia University campus from September until May. In the beginning that piece was a performance of an unbearable burden, but people began to help Sulkowicz carry the mattress, and in those gestures of solidarity I began to imagine how art can serve as a nexus. I wanted this poem to be a kind of coded call, an alert, a rallying cry if there is a rally to be had. But if my only choice is to testify alone, I prefer to do that in poetry, where confession has been put to powerful good use, for a change, reminding people that they at least have the right to their own stories.

I'm also thinking about what Maya Angelou has to say about anger and bitterness. I'm very moved by your poem about an abusive relationship, "Said the Poet," which ends, "Get down on your knees and say you’re sorry Have another drink Take off your clothes Try getting angry It feels so good." Do you ever feel like the poetics of fury risks reenacting the methods and rhetoric of the patriarchy? I ask because I've been thinking lately, beyond RUE, about where the awakening of anger takes us next? Audre Lorde looms large in my mind too. In "The Uses of Anger: Women Responding to Racism" she describes her experience, writing: " I speak out of direct and particular anger at an academic conference, and a white woman says, 'Tell me how you feel but don’t say it too harshly or I cannot hear you.' But is it my manner that keeps her from hearing, or the threat of a message that her life may change?" What kinds of changes may follow from expressing the truth?

~

Dear Kate,

Oh, that's such a good and hard question. I think of it as a question of genre or craft, rather than rhetoric: "Said the Poet" repeats phrases, or versions of phrases, I've heard under the umbrella of patriarchal rhetoric, but through the genre of poetry, where that kind of power might be defused. However, re-casting that kind of language in a poem, or putting form to violence, sheds light, I hope, on the nature of gaslighting and abuse, and is a kind of reclamation or challenging of that kind of rhetoric. If we say it out loud, if we put it in writing, it becomes less powerful, because it is us and not the oppressors who are saying it. It tells me both about the kind of violence that lives inside the abuser, and helps me to see more clearly why I felt so destroyed by it.

I think one of the worst things about suffering abuse is the silencing of it. We may not want to repeat what has been said or done to us in the fear that it will worsen the abuse, or put us in more danger than we were before. After all, studies have shown that legal action against abuse often risks the life of the abused person. That poem is my way of saying, yes—this happened to me, writing it is a way of deactivating its firepower, and speaking it aloud is a step toward healing.

In several of the poems in Rue, you discuss the complicated nature of famous men who both made important discoveries, marveling at the natural world, but who expressed blatantly racist views, who “sold their bastard children to orphanages.” Do you consider poem-making an act of historical revision? An act of revolution?

~

Dear Jenny,

My goal in my poems is to tell the truth, and in so doing, to believe in the possibilities that exist between us. When I was a polite liar I couldn't see which of my relationships were really relationships and which were mirrors of performance. In that addled state I started talking to the plants growing on the fallow field of my farm. I learned many of those plants had historically been used for birth control and this was a revelation to me—the fields were full of activists that midwives and witches had once used to “provoke the menses,” as the euphemism goes. It was like there was a Jane Collective of radical feminists providing underground access to abortion blooming out my back door if I could learn how to listen.

But learning how to listen also meant learning to hear the devastating role of biocolonialsm and botanical voyages of discovery on indigenous peoples. It meant realizing that even as I am charmed by Carl Linnaeus’s sketchbooks or his openness to the unknown when it came to marvelous plant and animal beings, I cannot turn away from the ways this thinking was tied up with his invention of racist human categories. Similarly, there’s a lot about Rousseau’s radical political visions that I admire, but I think the way he treated people with less privilege than he had tells us something about his ideas that we shouldn’t ignore.

There is a narrative that unfolds throughout your poems between a character, Ophelia, struggling to resist a demogorgon. Ophelia’s story in these poems seems to have strong parallels to what you wrote about coming to believe in your own truth and power. Did you feel like you and/or your life changed through the process of writing these poems? Thinking about your earlier remarks on writing as a way to send out signals to the others, as a way to offer friendship or warning or protection, I'm interested in whether or how you think poems might assert a kind of transformative agency? To put it another way, are your poems are spells and if so, what kind?

~

Dear Kate,

When I was thinking about the muse and the subjugation through the history of literature of the female body and female "madness," Ophelia came to mind. I had already written a couple of Ophelia poems in which I had imagined her as a kind of sister, as a person whose depression and anxiety had been spun into a pretty flowery dance that ended with her in her own self-made grave. I thought, of course, Shakespeare got it all wrong, and I don’t mean that in any way to dismiss self-harm, but rather to challenge his decision to consider that Ophelia’s most logical end. What I want to investigate is not Ophelia’s experience of suicide or suicidal ideation, but the male writer’s infliction of suicide upon her. The real Ophelia, who is many women I know and the woman I think I sometimes am, might be allowed to be more fully herself. I read a male critic who wrote that without Hamlet, Ophelia has no story of her own, and thought, what a crock. So I set out to transcribe all of Ophelia's lines, without the context of her father's or her brother's or Hamlet's, and what I saw there was a story about gaslighting—so, the poem with the 20-sided die is a cento of her lines that I think tell their own story. I began to imagine an Ophelia who could be equipped with a more modern-day sense of mental health awareness and with a clearer understanding of the ways in which Hamlet had gaslighted her—an Ophelia with friends—an Ophelia who was a dungeon master. This Ophelia, who was also me, also my sister, also my friends who had seen me—did change me, I think. In writing these poems I became her, and I became stronger.

I hope these poems are spells—I think of them that way—they are spells that transform the self, rather than destroying the other. The demogorgon and Ophelia are both operated by larger forces—societal and cultural expectations that lead us toward silencing, the mistrust of the self, and, in the case of the demogorgon, toxic masculinity. In writing the poems I was saying spells to destroy those forces and to resurrect a kind of self who was brave enough to confront and conquer them; though I can't say that I am that strong or brave in my own life, perhaps the poems can serve as conduits.

Thank you, Kate! I'm so excited about your book!

~

Dear Jenny,

I’m so excited for everybody out there in the world who gets to read your book for the first time. They are going to be transformed!

Love, Kate

Jenny Molberg’s poetry collections are Refusal (LSU Press, 2020) and Marvels of the Invisible (winner of the 2014 Berkshire Prize, Tupelo Press, 2017). She is the recipient of a Creative Writing Fellowship from the NEA, and her work has recently appeared or is forthcoming in Ploughshares, Gulf Coast, Tupelo Quarterly, Boulevard, and other publications. She teaches creative writing at the University of Central Missouri, where she directs Pleiades Press and edits Pleiades magazine.

Kathryn Nuernberger is the author of three poetry collections, RUE, The End of Pink and Rag & Bone. She has also written a collection of lyric essays, Brief Interviews with the Romantic Past. A recipient of fellowships from the NEA, H. J. Andrews Research Forest, American Antiquarian Society and the Bakken Museum of Electricity in Life, she teaches Creative Writing at the University of Minnesota.