Mapping the Body in Jena Osman’s Motion Studies

by Madeleine Wattenberg

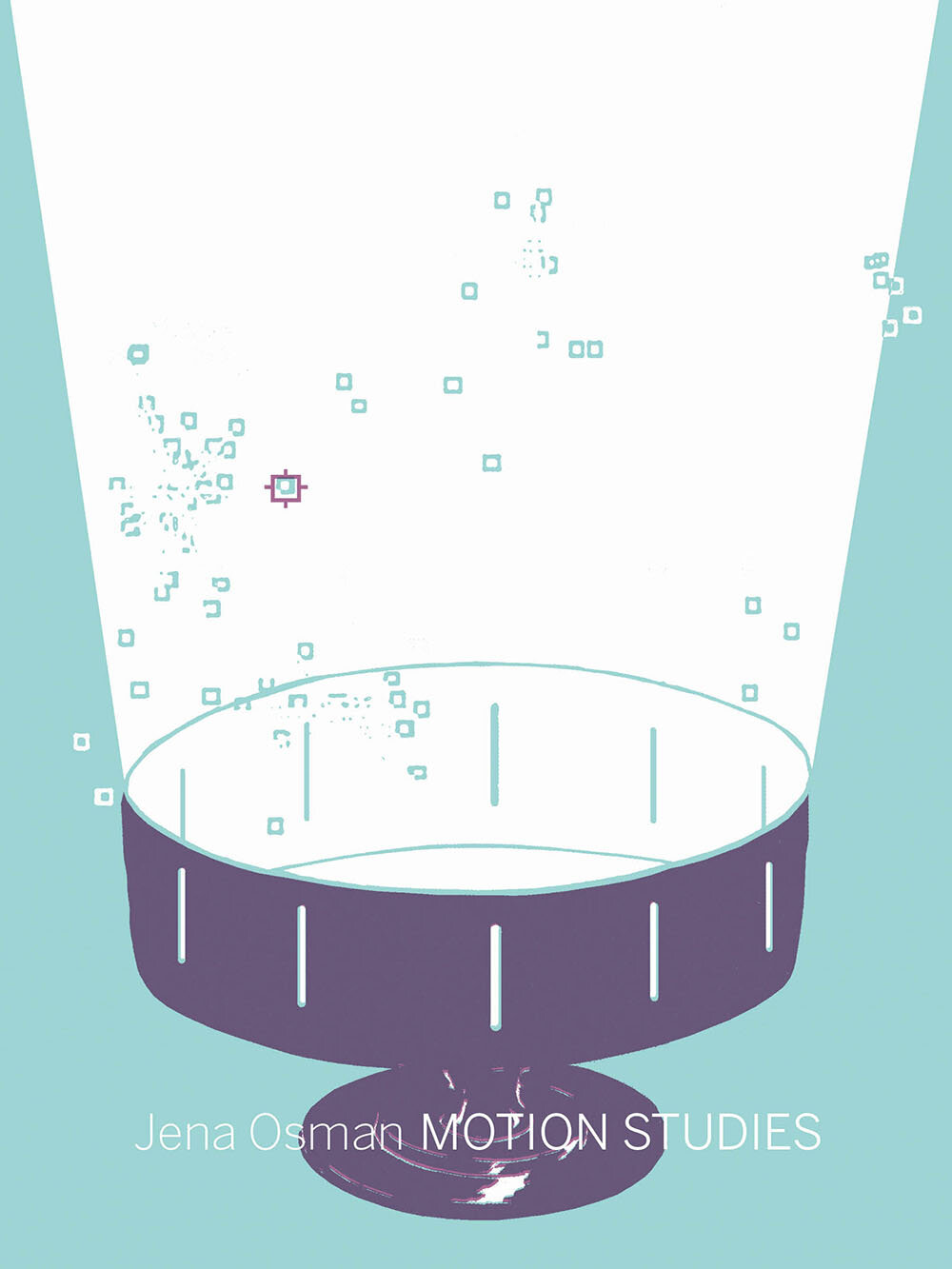

In Motion Studies (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2019), Jena Osman embraces textual hybridity and intertextuality in order to trace the evolution of technologies that map bodies’ movements and interiorities. The collection comprises prose sections, images and graphs, textual collage, speculative narrative, and lyric. These different forms destabilize both genre boundaries and assumptions about where concepts originate. Despite its variety in strategy, Motion Studies is tightly united by its concerns with the consequences of moving material bodies into representation.

In the title section, her starting point is Étienne-Jules Marey, a nineteenth-century physiologist who used a variety of methods and machines in order to graph bodies’ motions. Her end point is speculative, where the line between the present and the future blurs, where failure to generate a coherent digital narrative of the self has deadly consequences. Disjunctive turns toward new textual modes are grounded by Osman’s consistency in repetition and order. She concludes each description of Marey’s experiments with a sentence about a bird (potentially the very bird for which Marey creates a myographic harness in order to track the motion of flight). These sentences shift the conversation into a space of speculative imagining and theorizing.

The bird is interrogated by an “analyst” as it adopts and inhabits the roles of a variety of film characters: “I’m kind of nervous when I take tests, says the bird. The analyst says, Please don’t move.” Each film referenced by Osman uses motion tracking (such as Avatar) or incorporates an element of predictive policing (such as Blade Runner). A reoccurring reference is Minority Report, in which psychic prediction allows agents to arrest criminals before they’ve committed crimes. The result is that the history of graphing, tracking, and datamining is revealed to have always been speculative in nature—futurist imaginings have present consequences.

Following these prose sections, Osman uses a combination of lyrical prose and poetry to narrate the story of two characters, a “she” and a “he,” on a quest to “disappear beyond the company horizon” after winning tickets to have their data records wiped clean. We learn that they have been unable, despite their best efforts, to generate marketable presences online—they have failed to cohere. They are in search of the “New Wilderness,” an off-the-grid existence, a place past the horizon where it is possible to live without surveillance, data upload, likes and clicks.

Osman’s prose sparks against her lyrical shifts, and charged statements resonate across passages. She describes one series of photographs in which Marey depicted smoke reorganizing around various obstacles in order to track airflow: “they captured a continuity flowing around a stasis, and in that way they mapped time.” Later, the smoke reappears in Osman’s speculative narrative:

In this procession

they are bits of torn paper

cut-outs in shadow

seen from above

as ribbons of smoke.

A few page turns later, Osman describes Marey as an early data miner. She writes that “each move we make creates a line drawn, a filament of smoke: addresses, driving records, voting registration, credit card purchases, bank card transactions, health care records, web browsing histories, social media posts. The aspiration for the datamined profile is a mirror image of the subject through smoke: to pass the test, to be a real human. The reality is more likely an error-prone doppelganger, made of bits and pieces.” The speculative narrative puts into practice the consequences of Marey’s experiments. It also becomes possible that Osman’s fictional characters are these smoke-formed doppelgangers.

As in any process of translation, the relation between the source and its representation necessitates ethical considerations. How will the representation alter or erase the represented? Osman highlights how the metaphorical language of tracking implicates itself. Consider tracking, but also captured in film. Is representation a form of captivity? On Marey’s attempts to capture flight using the harnessed bird, Osman writes: “Was the bird really free?”

Motion Studies’s two additional sections also take up the question of mapping, representation, and scientific accuracy. In the second section, “Popular Science,” Osman considers phenomenology through founds texts and Walt Whitman’s ghost. The emphasis on the brain is then mapped onto a coral reef in the book’s final section. This final section, “System of Display,” draws a direct line from nineteenth century technologies to contemporary ecocriticism: “While nineteenth-century lectures on ancient coral reefs are carefully preserved in manila archival folders, twenty-first-century data on climate change is scrubbed from public view.”

In key ways, Osman’s collective examinings argue against what Jean Baudrillard might call the hyperreal—the postmodern state in which only interactions between simulacra remain, self-generated, without reference to an origin reality. To develop his discussion of simulations and simulacra, Baudrillard references the Jorge Luis Borges’s story “On Exactitude in Science.” This story describes mapmakers determined to create a map so accurate that they design a one-to-one representation of their Empire. Yet the Empire’s citizens find a perfect representation redundant, and soon let the map erode in the natural elements. In Borges’s version, the representation rots, and the real world carries on. Baudrillard flips the narrative—the “map becomes the territory” and it is originless, a system of self-referencing references.

As Marey’s experiments evolved, Osman describes a resulting absence of the body itself: “Understanding the mechanics of the body required getting rid of the body. Thus, a body reduced and transformed to points and lines in a system of flow. A body drawing its own trajectory, its own output.” We are more concerned with what the smoke flowing around the object suggests about the object than the object itself. The consequence is that we only engage with outputs, streams of data that corporations suggest define us much more than our embodied existences. It is the data that determines the “realness” of the human, not the other way around. This is appealing in that it avoids issues of essentialism, but to ignore material bodies altogether is to deny material forces, non-human agencies, the self-forming and evolving coral reef, the rising sea.

Borges’s story can be read through an ecopoetic lens too—it’s notable that it’s the sun and snow that erode the map—the material world interacts with and is capable of altering what purports to represent it. When Baudrillard flips the map, the material world is set adrift. The idea isn’t that bodies are essential and unalterable, but that in order to recognize how we do alter them, we must first recognize embodied existence within a material world imbibed with meaning that interacts with but is not produced exclusively by the human. Metaphor may change the natural, but “[a]s Nature changes, so do metaphors,” Osman writes.

In both her scholarly and speculative prose, Osman prompts the questions: Who is constructing the narrative and for what purpose? And what happens to the material body subjected to these mapping processes? Marey’s projects in motion were used by the military to determine absolute efficiency before bodily collapse. Ankle monitors track motion, so that, as Osman notes, breaking the rules of the device (not committing a crime) prompts arrest. Osman asks, “Can the device interpret the world?” The collection has immediate political relevance. I thought of twitter bots and Hong Kong protestors disabling facial recognition software in their iPhones to escape police.

When the characters in Osman’s speculative narrative reach the New Wilderness, they watch as “the world begins to erase itself, then redraws back to the wild, only to disperse and decay again.” Perhaps they are only data points, arranged and rearranged by page turns out of their control, dissolutions of absented bodies. As they travel, “the wild refuses to cohere as a clear picture. And yet everything quiet, everything still. Just a sliding from one lens to the other.” Is there a point where two worlds, two people, two pixels, map and mapped, collide? Collaborate? What’s the difference between a flipbook and a motion-tracking camera uploading pixels into a government database? Between a page’s white space and a gap in the frames? How do we make formulations from disparate points, from stars? And who will be guided by them?

*

“Is a Threat Like a Bird on Glass?”: Connect-the-Dot Poems from Jena Osman’s Motion Studies

Rather than connecting the dots in these images, I wondered what it means to have phrases, ideas, quotations as lines that “complete” the bird-narrative. In the first image, I paired the numbered dots with movie quotes spoken by the bird in Motion Studies (mostly from Blade Runner). In the second image, I pull Osman’s own lines. The rusty “stains” are from scanning each image with an app on my phone and not being able to get my body out of the way—my hands and phone's shadows are scanned, thus simultaneously represented and absented in the final product.

Images by Madeleine Wattenberg with text from Osman’s Motion Studies - click to enlarge

Madeleine Wattenberg's lifelong dream of writing a review entirely in emojis feels closer than ever. Her poems have recently appeared in journals such as Best New Poets 2017, cream city review, The Seattle Review, DIAGRAM, Fairy Tale Review, Ninth Letter, and Mid-American Review. She is currently a PhD student in poetry at the University of Cincinnati.