Review of Alison C. Rollins’s Library of Small Catastrophes & Catalogue Cards of Themes

By Jen Town

I was drawn to Alison C. Rollins’s Library of Small Catastrophes in part because of the arresting cover: a figure in a suit of buttons with an abacus mask, one eye staring out through the rungs. It’s artist Nick Cave’s Soundsuit (2008). You can see the one eye, two brown hands, and heels, but most of the body is concealed by this collection of multi-colored buttons, which made me think of the button box my grandmother had in her house, a tin box that opened to reveal pearl and wood, metal, bits of string. The box had—has, as it now lives at my mom’s house—an indescribable smell that I recognize as simply old.

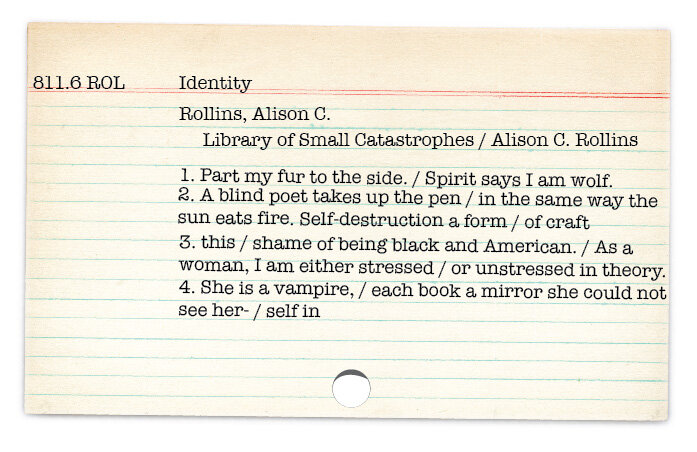

I was also drawn to the word library. Rollins’s book is about what we collect—we as individuals, sure, but also as a people. Let’s call this what it is for most people, for most eons: trauma. The first poem, “A Woman of Means,” starts with “Venus Hottentot,” the woman who was paraded around Europe as a representation of other, both female and black. She was called Sarah Baartman by white men. Her birth name: unknown, unrecorded. The speaker of the poem is subjected to a pregnancy exam but in the end states, “I give you permission to enter— / the opulence of this rabbit hole.” Sarah Baartman, whose name is not Sarah Baartman, was never asked for consent, never granted it.

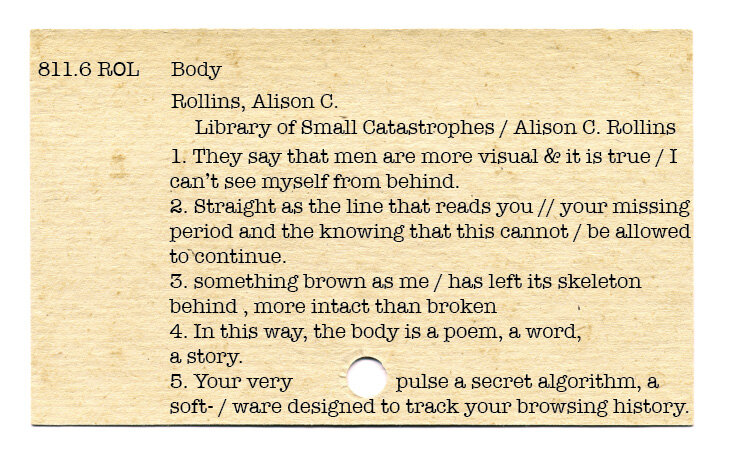

Many of the catalogued traumas in Library of Small Catastrophes are bodily. “It is cold in this thing we call a body,” we learn in “Skinning Ghosts Alive.” “We are never our own. // This is why we are so lonely.” The poem “Fultz Quadruplets,” about the birth of the first black quadruplet twins on record, begins:

The God is a white man.

The white man is a doctor.

The doctor is the one who

names things.

Again we see the importance of naming and who is doing it. These poems seek to name, to record, to remember. The poem “Water No Get Enemy” is dedicated to Hondaran activist Berta Caceres, who was assassinated by American-trained Honduras military (the eight men charged with her murder have had their trial suspended indefinitely) for her role in protesting four hydro-electric dams on the Gualcarque River that would threaten traditional livelihoods for indigenous peoples. “The men own even the rain: / even the wet body, found with head full / of black curls rippling like waves.” “I sing/ the body hydroelectric” is a clear allusion to Whitman’s “Song of Myself” (and not the book’s only Whitman reference).

Like Whitman in Song of Myself, Rollins is striving in Library of Small Catastrophes to encompass a broad swath of what it is to be here and human. She approaches this task from various angles: poems that directly record the experiences of people whose stories are at risk of being lost; by weaving together the personal and the political (which we know, is also personal); by defining and redefining words like “misery” and “mercy”; by writing a poem about the end of a marriage using 100 lines from 100 different female poets (“Cento for Not Quite Love”). To use a phrase I heard a lot in undergrad and grad school, there’s a lot to unpack in Rollins’s book, and I feel as though I’ve just scratched the surface.

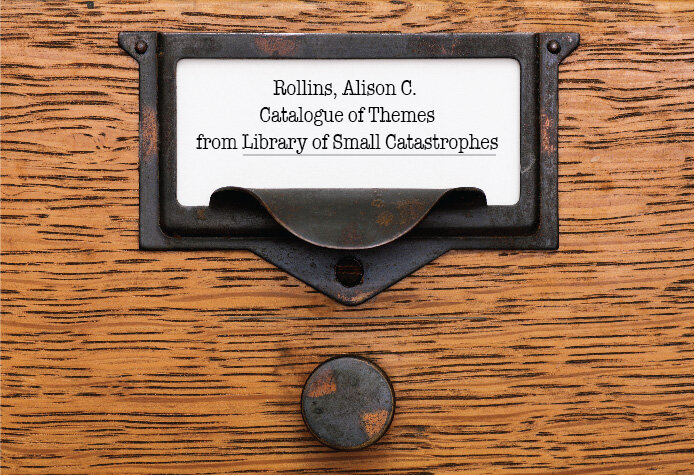

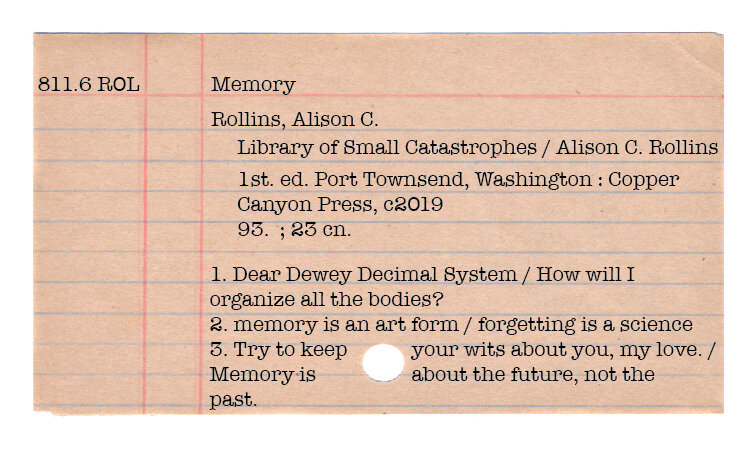

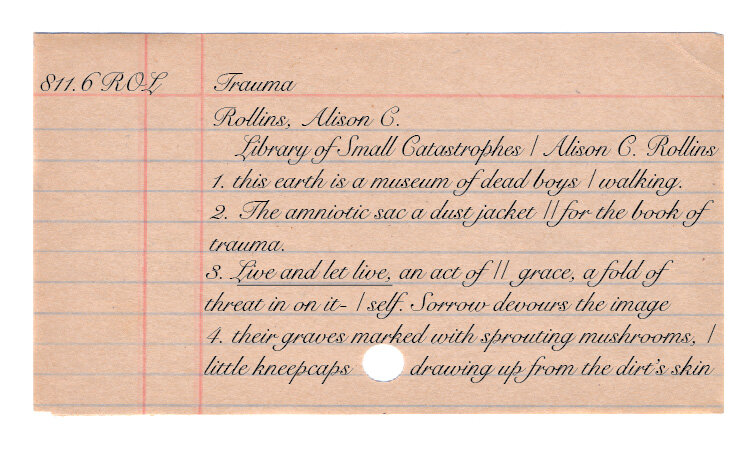

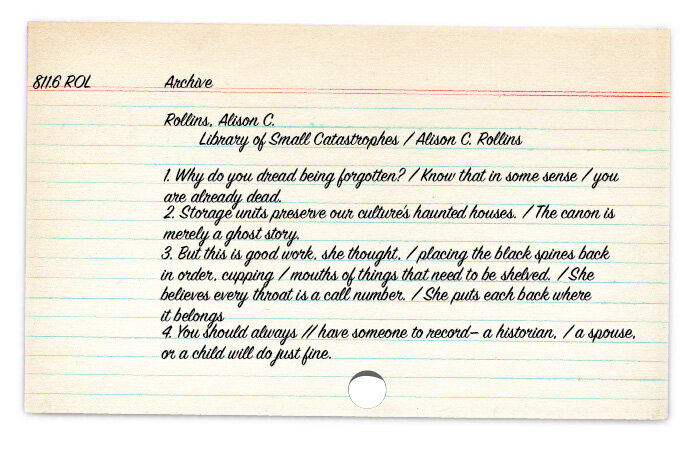

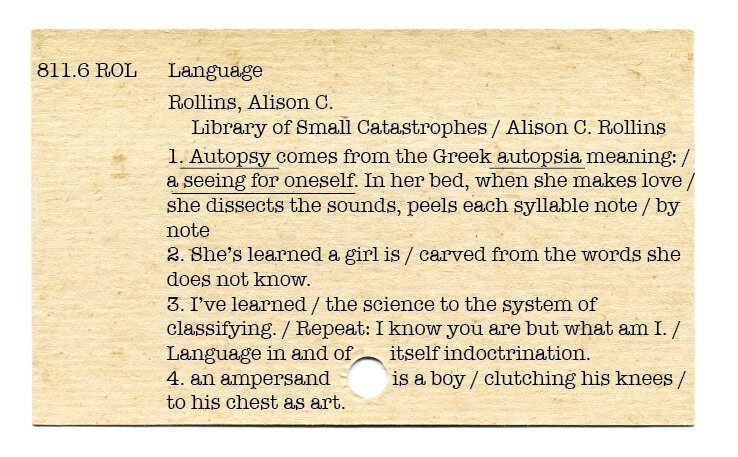

To continue my excavation, I created a poster for Rollins’s book that represents some common themes (in no way exhaustive) and identifies lines that feel representative. I organized these lines—a library being, first and foremost, a way of organizing information—as subject catalogue cards. It’s been a while since I practiced writing catalogue cards as a 4th grader (back when there were still wooden card catalogues in our local library branch—which was in a store front in the Millcreek Mall) and I took artistic license with some of the details. As I hope the poster illustrates, Rollins’s poems are weighty, strange, full to bursting, inspired, musical, and various. They, dare I say it, “contain multitudes.”

Jen Town's poetry has appeared in Mid-American Review, Cimarron Review, Epoch, Third Coast, Crab Orchard Review, and others. She earned her MFA in Poetry from The Ohio State University in 2008. Her first book, The Light of What Comes After, won the 2017 May Sarton Poetry Prize from Bauhan Publishing. Jen lives with her wife, Carrie, in Columbus, Ohio. You can find her online at jentown.com.