“the vertige de language”: A Dialogic Review of Erín Moure’s Translation of Wilson Bueno’s Paraguayan Sea

by Christina Vega-Westhoff & George Life

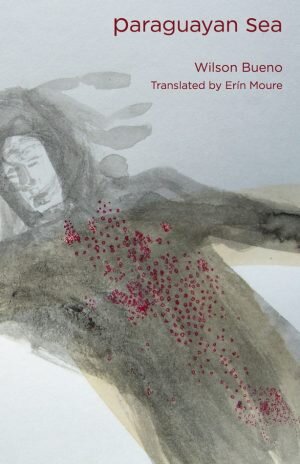

Paraguayan Sea is Erín Moure’s translation of Brazilian author Wilson Bueno’s 1992 classic Mar Paraguayo. Written in Portunhol (a mix of Spanish and Portuguese) and Guaraní (an indigenous language of Paraguay and surrounding regions), and translated into Frenglish (English imbricated with French), Paraguayan Sea stages a polylingual monologue of love and tragedy set in a Brazilian beach town, delivered by a fluid and floozy narrator, exuberant and fragile. Enriching the pleasure of the text is an array of paratexts by numerous authors, from introduction to commentary to interview to glossary, offering an unparalleled reflection on the process and politics of translation.

CVW: “What happens when you turn a polylingual novel outward and make it speak to readers on the street?” asked Andrew Forster at a discussion and book launch for Paraguayan Sea at Concordia University in Montreal. This event was part of an outdoor exhibition by Forster in collaboration with Erín Moure that presents text from the book on yellow bands stretched across a campus building that faces downtown. Later, at least one person in the audience said that was why they were there, having passed by and seen one language in particular, Guaraní. Early in the discussion, Forster mentions and questions approaches to the text. In answer, I wrote:

ritual space of the book

longitudinal stretch of language

or you can burrow into the language

you can stay in one place and go through the membrane into the imagination

I’m curious about the ways we approach reading Paraguayan Sea. I’ve felt ambulatory in my reading—wandering, reapproaching, and accompanying. I think your approach is more of a burrowing, looking things up along the way, pausing intentionally.

GL: You’ve been circling the book, then, like a pedestrian might circle, or recircle, the building? I’ve moved in that direction but began very slowly, trying to orient myself. Where is Paraguay? What is Portunhol, Guaraní, a catin? Is “I’ai” made up or Romanian? If it’s Romanian, why is there Romanian in a text in Portunhol with Guaraní translated into Frenglish? What is Frenglish, anyway? Why does “birrd” have two r’s? I began with my laptop open, looking things up. Eventually I found a PDF of the original online and began reading what I could of the two together. Maybe that’s a form of burrowing, that back and forth, or borrowing. What, though, I wonder, is “the ritual space of the book”—of this book, not Mar Paraguayo but Paraguayan Sea?

There’s a ritual in the rhythm created that reawakens or activates the gaps and embroidered textures in the narrative.

CVW: I loved the elucidictionary at the back—did you consult it as you read? There’s a ritual in the rhythm created that reawakens or activates the gaps and embroidered textures in the narrative. It also stands firmly on its own, with separate delight. How might this inform a space, a translation? I feel a propulsion outwards as in meanings and associations continuing, touchstones.

The two rr’s was a moment of major excitement! Later, I did want to look things up. But not plugging into a sentence to reconsider “meaning.” I went looking for possible connections between Reinaldo Arenas (his Pentagonia) and Wilson Bueno. In both, narrative and narrators are always shifting, shaking, the frog that gets all antsy before it eats its skin. Did you just say word soul across the room? Language incidental, integral. Mirar mar Sea see, now I’m notetaking.

GL: Sí, así es. “Suruvu is the word-soul turned birrd,” a clause followed by a colon and a sentence that flows on for sixteen lines. In the original, birrd is “párraro,” which sounds like a mix between pájaro and parrar, “bird” and “stop” in Spanish.

CVW: Also, párraro, I think, is Portunhol/Portuñol. When does Moure translate Portunhol to Frenglish/Franglais—here the double rr seems to be what was moved, retained in another impulse. Time and characters move fluidly in Paraguayan Sea. Are there three? Dog and old man and floozy? Oh, young man.

Did you research paraná? I am wondering about Paraná and Dnipro and Mississippi. River town ocean.

GL: André Sjens talks about paraná in his postface at the back of the book. It follows the glossary (Bueno’s “elucidário,” Moure’s “elucidictionary of the Guaraní langue”), and reads like an overflow, exfoliation, or effulgence of the gloss for paraná: “river that runs to the sea; river the size of a sea, river that is reminiscent of the sea, river that crosses to the sea.” It occurs to me, turning the page to see if the definition continues onto the next (it doesn’t), that in the dictionary paraná sits between Paraguay and pará. Pará is “sea (in old Guaraní); hue of several colors; polychromatic spaces.” Hence, it would seem, Paraguayan sea? Paraná is of at least triple significance, as Sjens explains. Principally, it refers to the river that serves along two stretches of its course as a fluid international border, first (if we follow it from its source) between Paraguay and Brazil and second between Paraguay and Argentina; additionally, it’s the name of a Brazilian state and an Argentinian city, both of which border the river. It’s in the state of Paraná that the novel is set, specifically in the beachtown of Guaratuba. For Sjens, this Paraguayan sea holds, in Moure’s “mourE(orless)nglish,” a “mar/sea/mer phonic drink, as might be found in shipwrecked bottles holding messages.” This is word as aqueous (s)play, or spray (array), a chromaticism of imbibition. The double r as in birrd, as in err. Translation, then, as fluid infection, inflection, an instep or inlet-meander.

CVW: Where does the language take us in relation to these waters? Para and pará, ghost waters in some sense of moving between. Do you see the little anchor in “mourE(orless)nglish”? Pulling the sky right down. And really what a beautiful invitation. All the echoes of little dog. Perrito. Brinks. Specified water noises. Education, listening, and floozy are revolving for me.

Maybe I should be more specific. I am thinking about Moure saying something to the effect of Guaraní being the indigenous language most spoken by non-indigenous people in Latin America and that it is taught in schools.

I am thinking of in whose presence a language shifts from interchange and the context of this book now in North America, and in the U.S. The snow is really coming down now. Lake Erie. Niagara River. Lake Ontario. St. Lawrence. Atlantic. Names I know. Poured over the ones I don’t/am learning.

GL: Moure writes in her commentary that “the book is a displacement of a displacement and a homage to displacements.” Paraguayan Sea becomes a northward migration and purposeful recontextualization of Mar Paraguayo. On one level, Moure’s Frenglish reflects the linguistic topography of Montreal, where she translated the book. Yet it’s not published in Montreal, or even in Canada, but in the U.S. This displacement adds to the cross-border turbulence of the work. In an essay on translating the Galician poet Chus Pato, Moure speaks of such turbulence as perturbation: “What interests me are the perturbations that can result in the language of arrival: for me, translation has to perturb the complacency of my language” (My Beloved Wager). This statement occurred to me in response to what you say about the names one knows and how those names can erode or muffle those one doesn’t. I’m wondering how the erosional or muffling force of American English, the official monolingualism of the U.S., is perturbed or jostled by this book.

What/whose version of a language is taught, in what context?

CVW: As you know, I’ve been reading around in the book after rereading it (and oh, narrative, but mostly oh rhythmic tenacity! that the embroidered text takes us along with its gaps and knots) and thinking about an article in the New York Times today about the historical repression of Guaraní in Paraguay’s educational system, emerging attempts to revitalize the language and the difficulties encountered in that. What/whose version of a language is taught, in what context?

The Oxford Book of Latin American Poetry (2009), edited by Cecilia Vicuña and Ernesto Livon-Grosman, contains an earlier perturbation by Moure of the Guaraní into Kanien’kehá (Mohawk) and the soundings and rhythm and questions that are there in that. The excerpted translation is without a glossary, but what would a Kanien’kehá glossary imply or ask? I’m thinking of that in relation to the elucidictionary that appears in Paraguayan Sea (and all that is specific to place and worlding—all the sounds of water, water boiling, river bubbling, words specific to the actions of water, all the flying, mar y fauna colors). Language: always questions of for whom and by whom. When Moure returns to the Guaraní there are still traces of other versions, earlier rivering, path of, where the sea is not but is: “Make no mistake: Guaraní is as essential to this story as the flight of the birrd, the speck…”

In their preface, Vicuña and Livon-Grosman write:

In Western terms, a constellation is constructed from star to star. In the Andes, a dark constellation is the negative space between stars. The generative force of the cosmos, the space of creation, lies in the gaps between stars. This constellation, as well as the Mexican concept of nepantla, becomes a metaphor for the space between languages where mestizo poetry comes into being.

I am thinking about the resistance and complacency of language, what negative space may include. This need to take care with celebration, with construction. Of the ñandutí form of the book. Of the actual ñandutí (“fine weaving or brocade, a traditional Paraguayan lace; from a word for web of a small spider”) not as metaphor or image, but space. And our responsibility entering into that space as readers.

GL: Right, if language is water, languages don’t flow with equal freedom. Banks are widened for some while others are dammed at their source. Is language a resource? If so, which languages or what forms of them are available to whom and under what circumstances? In her commentary, Moure rethinks her initial version in which she translates Guaraní into Kanien’kehá. She notes her practical difficulty doing so, lacking familiarity with Kanien’kehá and resources for learning it. The ethical difficulty follows from a broader consideration of the practical one. That is, given the impact of over a century of colonial policy instituted in residential/boarding school systems in Canada, the U.S., and elsewhere, Indigenous peoples have been forcibly dispossessed of their ancestral languages.

Many contemporary poets of Indigenous descent in North America—James Thomas Stevens, Aja Couchois Duncan, Jordan Abel, Layli Long Soldier, for example—have commented on the irony of this situation in which, in order to reclaim their ancestral languages, they must resort to dictionaries and other language-learning resources compiled by Euro-American settlers. Guaraní has not been free from colonial interference but it is nevertheless co-official in Paraguay, enjoying relative parity with Spanish and Portuguese. It is spoken by Indigenous and non-Indigenous alike. What if this were the case for an Indigenous language in North America? What if Kanien’kehá were co-official in Canada or the U.S.?

Moure’s ebullient (n)ear-English suggests one vision for how English might minoritize itself by historicization and invention to make space for others.

This is the utopian transposition imagined by Moure’s initial version; it remains in the present book-length translation but Moure respects the autonomy of Guaraní, leaving it untranslated. This implies an analogous respect for Kanien’kehá. “Languages are not there for us to simply use, at times,” Moure reflects. “Why should a threatened language of Canadian spaces want to be in an unusual melee of a confessional novel by a Brazilian from Paraná, translated by a Canadian poet from Quebec? What is serving whom and how here? Whose identity is here spaced, spaced out, interspaced?” To my mind, Moure’s ebullient (n)ear-English suggests one vision for how English might minoritize itself by historicization and invention to make space for others, in particular those it has systematically repressed. Outlining, perhaps, a more open constellation?

CVW: We’ve had an ongoing delight in the floozy, overusing the word together. Though marafona is the word written, maryfauna is what I read, ocean and fauna, which is of course different. And yet it rings beside. I am tempted to quote from everything. In “And Poetry,” Moure writes, “My method? If anything, a kind of accretion. Sounds attract feelings and aches, and vice versa. Sounds and words attract each other. They attract, too, ideas and worries. And dreams. And they shudder a thread of remembrance that knits the self over and over again” (My Beloved Wager). Paraguayan Sea, particularly towards the center of the book, seems to bring forth this accretive autonomy of words—the cooing at the end of lines, stanzas ever smaller and larger, elation and humor:

the living knot: microscopic accentuation with which all and anything can get mixed up in a single and mécanique push of the needle: fatal: i stick it in and keep sticking it: like whoever stabs justice even if it’s slow: a stitch of finest crochet: ñandu: ñandutí: ñandurenimbó: a single solitary stitch to the web almost beyond ocular or human comprehension: ñandu: mobile stitches: minimal millions will escape from their eggs on the fragile ligne of this web: ñandurenimbó: ….

GL: If we had more space, it would be worthwhile to quote much more before and after this passage. Ñandu and its accretions repeat over a number of pages. The text does read as a swelling, a rising tide propelled and particularized by the Guaraní.

CVW: The relation between line and web and gap with orientations and conceptions of time; things emerge simultaneously. The time of the watch, the time of the stitch. Ligne: line, unit for watch movements, measurement, and feeling. Yes, we could expand the quote in either direction. How does the text move time through us?

GL: I just noticed that the text Forster excerpts for his banner is the same that you’ve quoted (“the living knot”). In a write-up on the event, Moure notes that two Paraguayans were in the audience, one of whom was shocked to see in passing the word ñandutí.

CVW: “Now here’s le trou: the hole of the hole in le centre.”

George Life is a poet, translator, and scholar living in Buffalo, NY, where he is writing a dissertation on contemporary poets' engagement with U.S. coloniality. Recent work has appeared or is forthcoming in Hambone, Circumference, The Emily Dickinson Journal, and elsewhere.

Christina Vega-Westhoff is a poet, translator, aerialist, and teaching artist living in Buffalo, NY. Her first book, Suelo Tide Cement, won the 2017 Nightboat Poetry Prize and was published last year. Her work has appeared recently in Words Without Borders, BAX: Best American Experimental Writing, and Emergency INDEX.